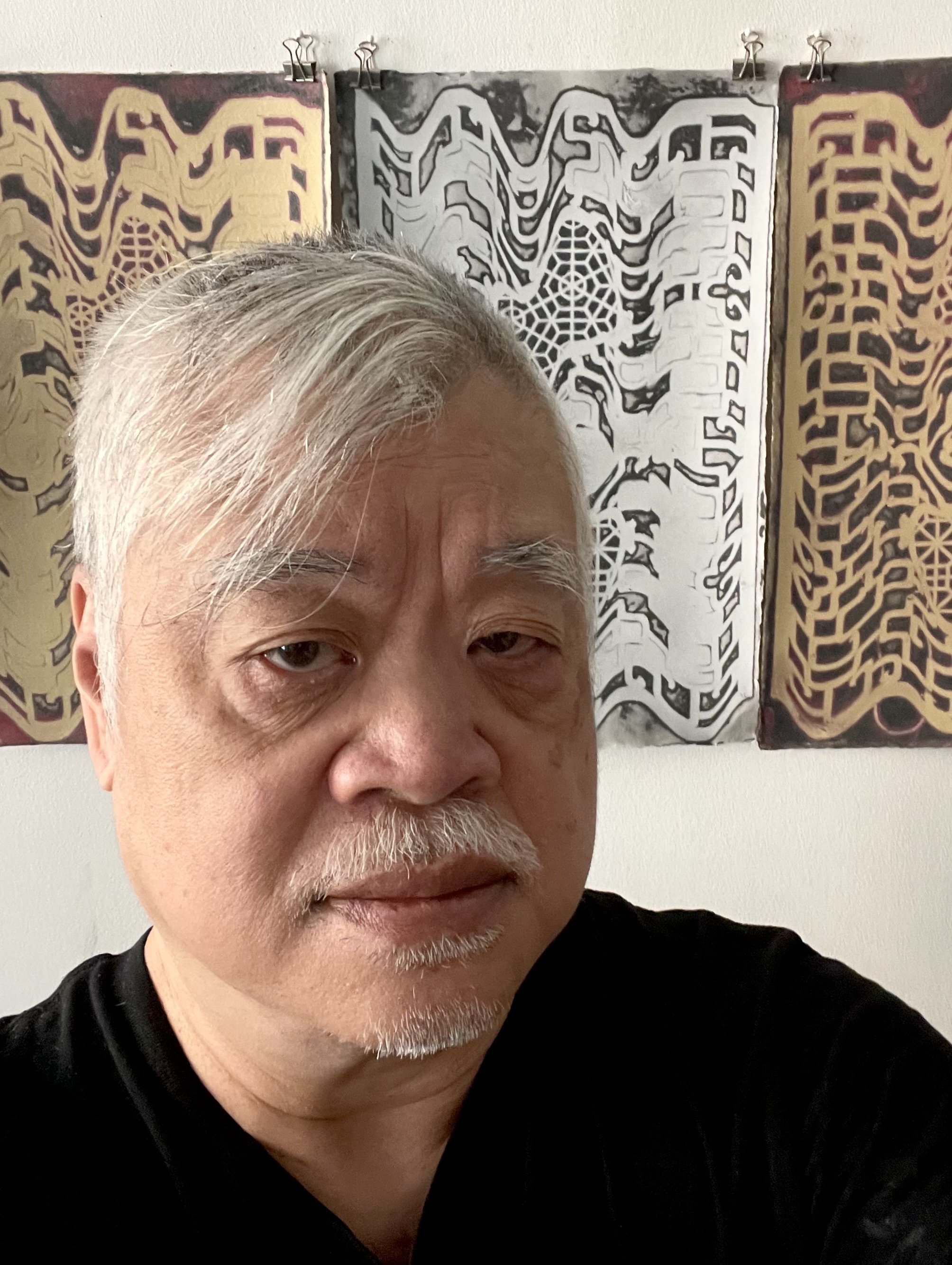

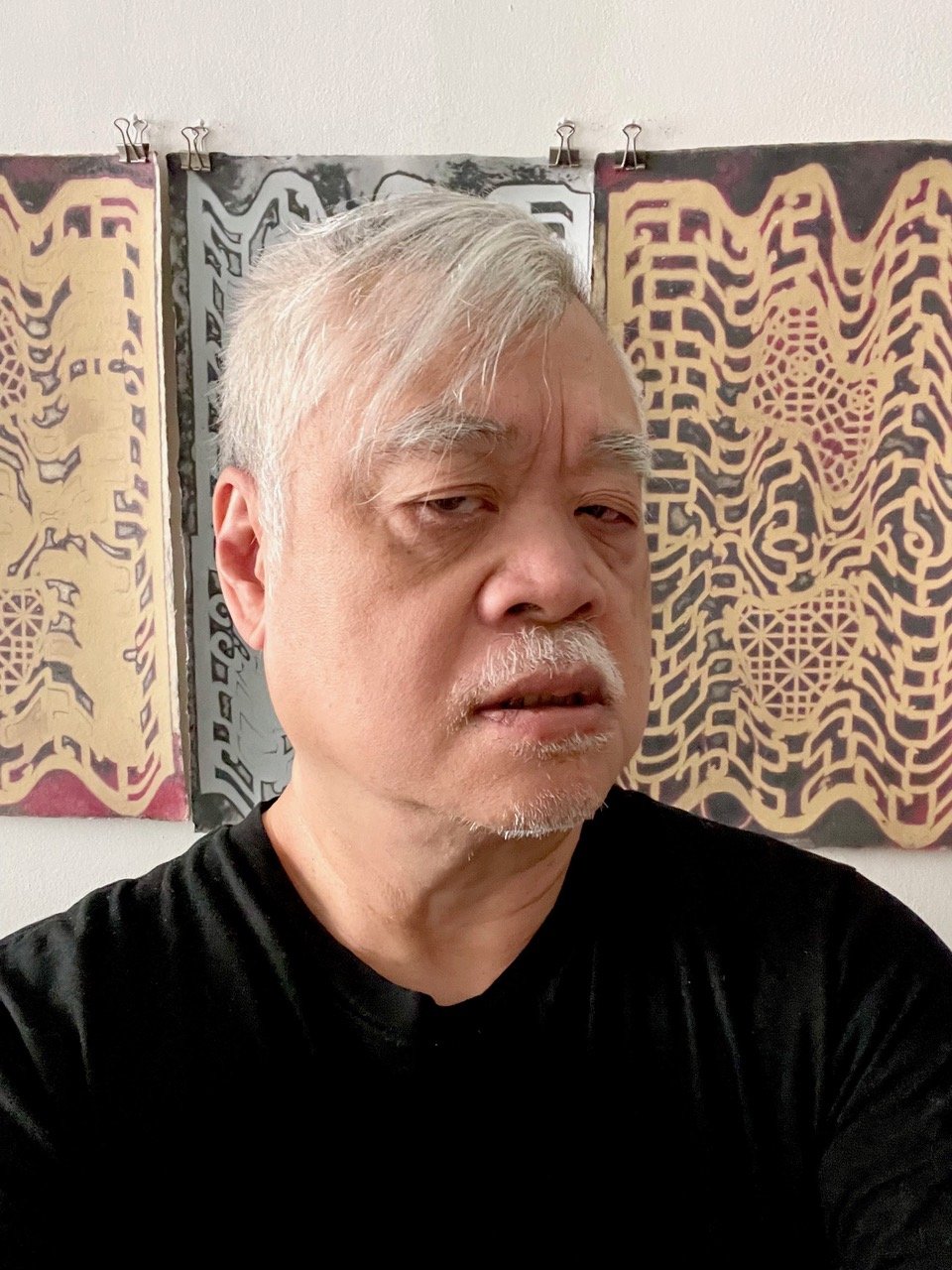

Paul Wong

PAPERMAKING CHAMPION

As the artistic director of Dieu Donné for nearly forty years (from 1978 to 2017), Paul collaborated with over 1,000 artists resulting in an unparalleled body of artwork using hand papermaking as a primary artistic medium. Working with emerging to well-established artists Paul helped shepherd each of their projects through to completion. Along the way he developed many creative techniques that are now commonly used in paper-art studios and classrooms worldwide, and trained many papermakers in sheet production and in the art of collaboration. In his own artistic work, Paul created a body of work including pulp paintings, paper sculpture, artist books, and large-scale installations, many of which have been the subject of important exhibitions. As a collaborator, artist, and mentor, Paul is recognized for his significant contributions to the creation of contemporary paper art.

Paul Wong

Essay by Sue Gosin

In 2022 the North American Hand Papermakers chose Paul Wong as a Paper Champion. For those of us in the Dieu Donné community, he has been a National Treasure for more than four decades. I have previously written about Paul’s vast contributions in my “Profiles in Paper” column for Hand Papermaking Newsletter in 2005 and for a 2013 article for Hand Papermaking magazine titled, “Conversation with Paul Wong: What Defines a National Treasure?” For this Paper Champion tribute, I will quote from these two essays to illuminate Paul’s early education and experience in hand papermaking and his role as a master collaborator spanning four decades at Dieu Donné. This is just part of the story, for Paul Wong is first and foremost an artist in his own right. I will conclude my tribute with a discussion of his brilliant artwork and his career as an artist.

I first met Paul in 1974 when the two of us entered graduate school at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Both of us focused our studies in the printmaking department and both of us came under the spell of hand papermaking. In early 1975, papermaking at Madison evolved from sheet production in Walter Hamady’s book arts program to art making. Paul learned to beat rags into pulp in “Walter’s” style as he had learned it from Laurence Barker who learned it from Douglass Howell. After the initial lessons, Paul began to cast pulp into sculpture. His art installations from this period were comprised of two-dimensional printed images and three-dimensional cast objects, the combination of which would reveal its full potential in his mature work decades later.

After receiving his MFA, Paul continued to make his own art in paper, working at Joe Wilfer’s Upper US Papermill outside of Madison where he was exposed to Joe Wilfer’s and Bill Weege’s ongoing collaborations with visiting artists such as Alan Shields and Sam Gilliam. When Paul joined a larger art community in New York City, he brought with him a penchant for experimentation and a communal style of sharing.

Paul joined me at Dieu Donné in 1978 with funding from the Tiffany Foundation and later from the NEA. The first year involved learning professional hand papermaking on the job. While assisting with the day-to-day production of custom sheets of paper and working with artists, Paul engaged himself in absorbing the research from the previous two years of study in fibers, pulp preparation, coloring, sizing, and drying at Dieu Donné. During this early time together, we established a pattern of collaboration with artists that has endured for decades. This one-on-one, hands-on approach afforded Paul a diverse engagement with hundreds of artists.

Some of Paul’s most vivid recollections are of working side by side with Joe Wilfer developing the first Chuck Close pieces at Dieu Donné in the late 1970s. Years later, Paul recalled the high spirits of the Dieu Donné team working with the Pace team led by Ruth Lingen (Joe Wilfer’s protégé) on Close’s magnificent, large-scale “Self-Portrait/Pulp” edition from 2001.

I asked Paul, what are the qualities that a good collaborator needs to help artists create their art. First, he said a collaborator must be “egoless” and always remember that you are working on someone else’s art. Next, you must be able to educate and expose artists new to the medium in a way that they can understand it. It is also important not to impose your ideas but to coax out of each artist an approach for them to discover. Most of all, it is important to help people overcome their insecurities about working in a new studio with strange assistants in a medium they are unfamiliar with, to make them feel comfortable. As an example, Paul referred to his experience with artist Ursula Von Rydingsvard who came to Dieu Donné with a background as a sculptor of stand-alone, monumental wood sculptures. As Paul introduced her to the intimacy of the medium and the ability of pulp to respond with great sensitivity to her vision, she “got it” and began to “start thinking for herself” without suggestions or guidance, ultimately producing a remarkable body of work quite different from her monolithic sculpture but nonetheless an accurate reflection of her inner voice.

It was a rare occasion for an artist to come to Dieu Donné with experience that matched Paul’s but an NEA-funded residency with Winifred Lutz provided an opportunity for a peer-to-peer exchange and a chance for Paul to observe an artist who had invented distinctive solutions for casting high-shrinkage translucent pulps such as flax and abaca. Working with Paul, Winifred created a beautiful body of original art that showcased the talents of two masters of the medium coming together.

Paul’s range as a master collaborator is best exemplified by his diverse projects with Richard Tuttle. Paul began working with Richard in 1987 when May Castleberry asked Dieu Donné to create the paper for a Whitney Museum limited-edition artist book, Hiddenness. Paul described how Richard brought in a sheet of paper with a green paint drip on it to show Paul what he wanted for one of the pages. To replicate the bubbly drip, Paul added methyl cellulose to the pigmented green pulp and agitated it to create bubbles as he poured the green pulp down the surface of a freshly formed sheet of white cotton. He held the mould at just the right angle to duplicate the directional flow of the colored drip. The next collaboration with Richard Tuttle in 2002 involved making one-off experiments using pigment-dipped strings and abaca watermarks that eventually culminated in an editioned suite of three images, titled Dawn, Noon, Dusk. In 2009 when Richard returned to Dieu Donné, Paul prepared brightly pigmented cotton pulp so that Richard could treat it like clay, literally throwing handfuls of pulp to form four distinct but related sculptures intended as a composition. For an edition of 19, Paul accurately reproduced the four sculptures retaining the spontaneity and high energy of Richard’s originals.

Throughout his career, Paul Wong has been also been a generous teacher sharing what he has invented and mastered with students at Dieu Donné as well as at workshops such as Oxbow, Haystack, and Penland. His lectures and interviews about hand papermaking reveal his vast knowledge of the field, his skill in collaboration, as well as his characteristic respect for the process and the people he has served.

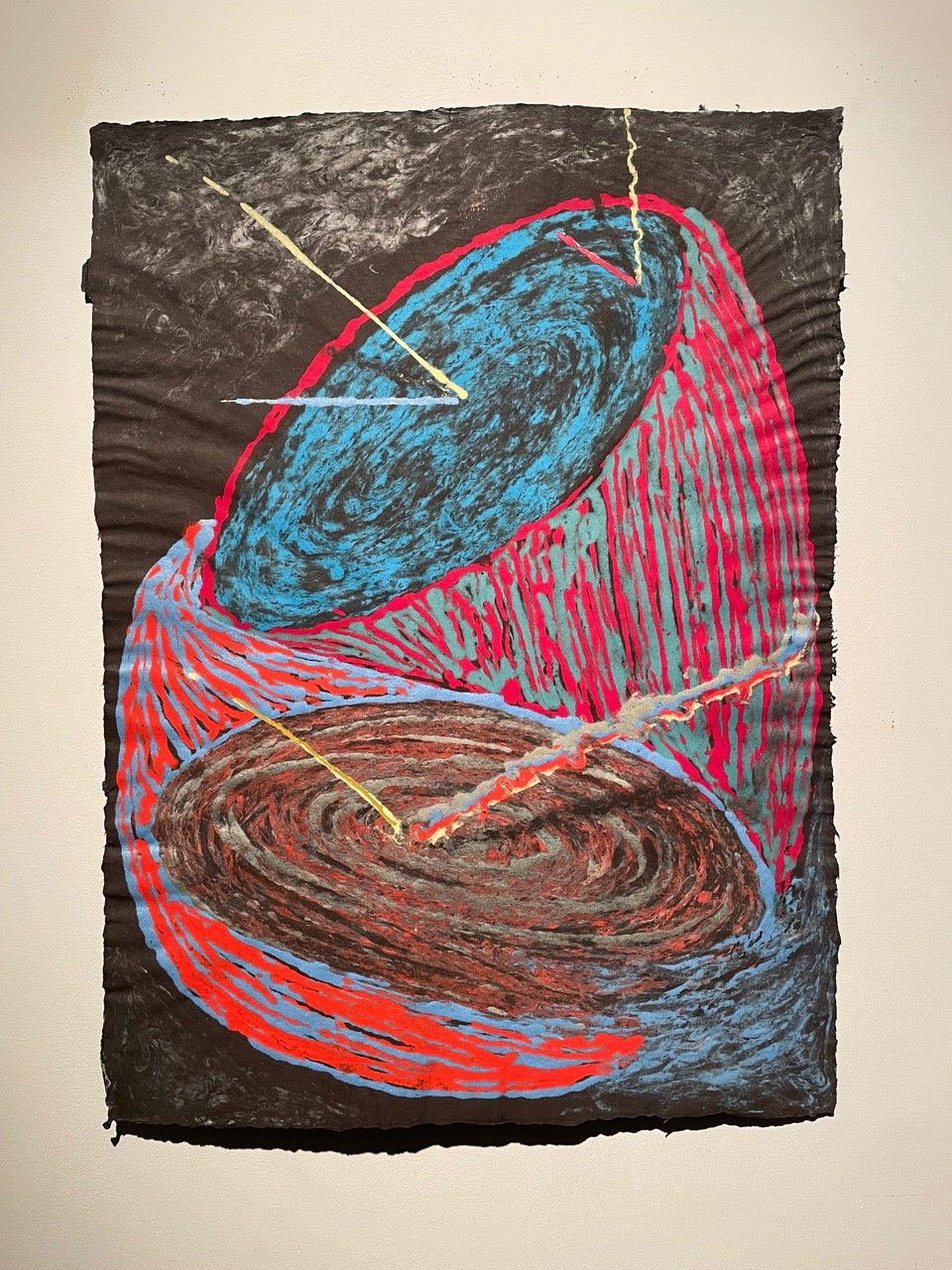

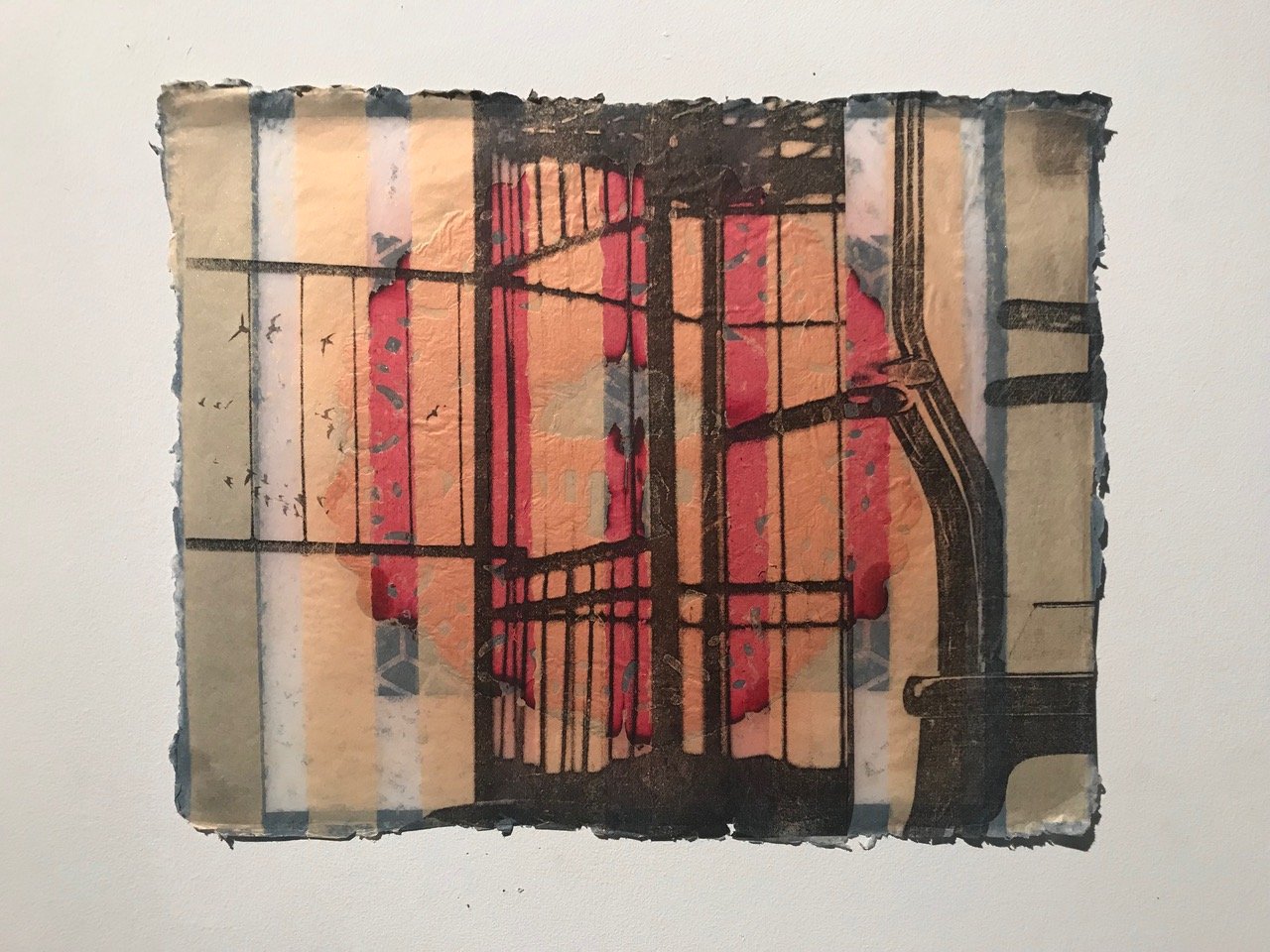

During Paul Wong’s years as a graduate student, his art practice was focused on printmaking combined with his interest in sculpture and installation. As early as 1977, Paul exhibited these concepts in a solo show at the University of Wisconsin. After moving to New York City, Paul created a series of powerful abstract images that displayed his exploration and mastery of pulp painting, watermarking, and stenciling on sheets stretched over kite-like structures. In 1981, he had the first of many one-person shows at the Condeso-Lawler Gallery in New York City. For the seminal American Craft Museum group show in 1982, Paul’s work was included with other contemporary artists experimenting with handmade paper such as Kenneth Noland and Chuck Close. In a review for Artforum magazine in 1985, Ronny Cohen describes how Paul’s work breaks down the barriers of craft and fine art and the traditional categories of sculpture and painting.

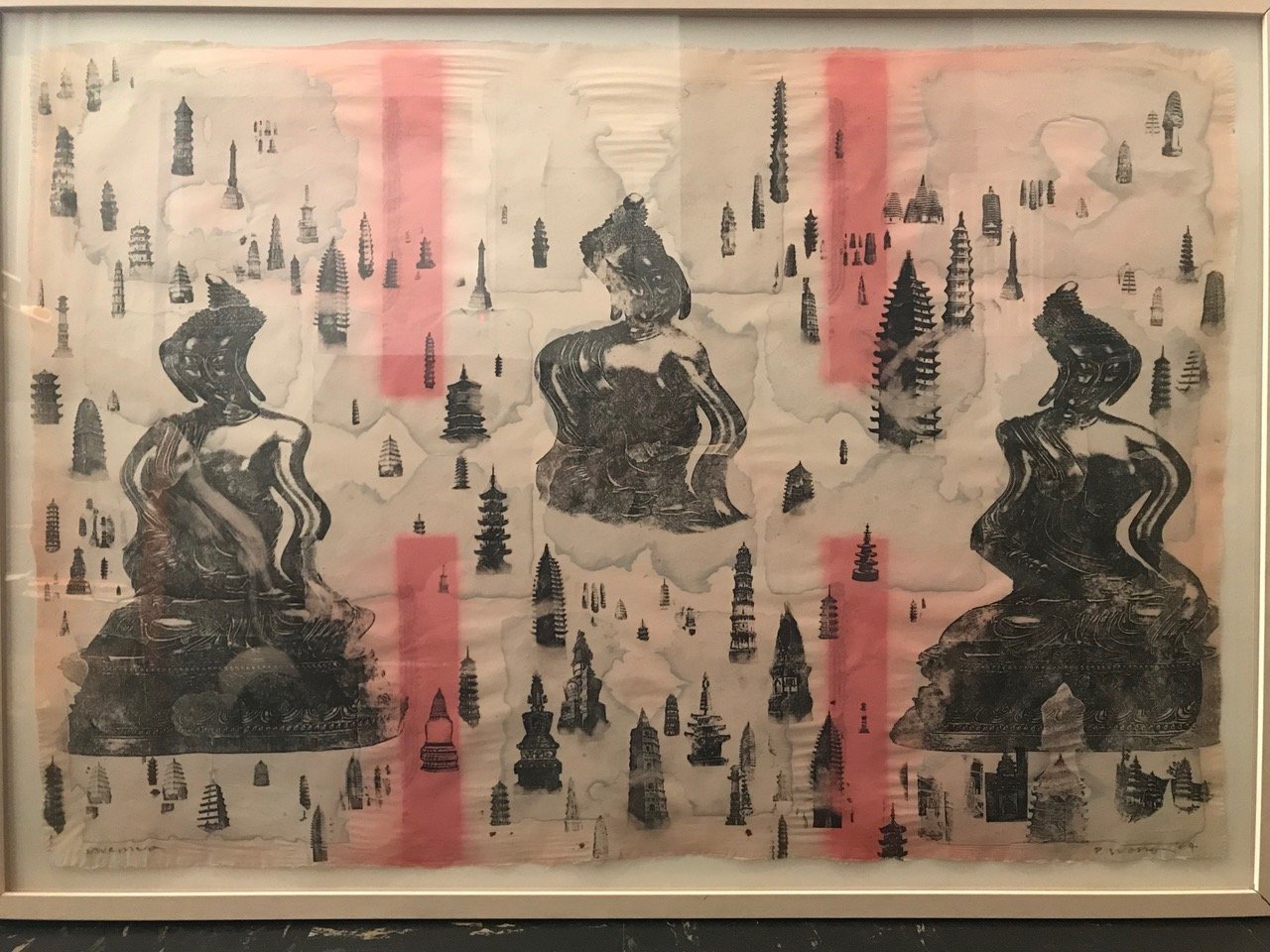

By the mid-1990s Paul began to integrate his style and technical skill with images from his personal history and Chinese heritage. An exhibition entitled “One Billion Ghosts” presented at The Dieu Donné Gallery in 1996 first showcased his growing research in Chinese cultural traditions, including early papermaking in China and the development of joss paper for ritual customs. At his 1997 Neuberger Museum (Purchase, New York) exhibition entitled “Burning History,” Paul fully realized in concept and execution his role as an artist within the history of papermaking in China and in his own time. The paper sculptures and paper/transfer prints he created for this installation take the viewer on a poetic journey through the cultural artifacts of highly charged symbols evocative of China’s past, its spiritual practices, his family history, and Paul’s personal identity as a present-day Cai Lun, re-inventing the process of hand papermaking as an art medium.

Paul continued to weave these themes of Chinese joss paper with the dramatic events of his family leaving Communist China to begin a new life as cooks and restauranteurs in the United States along with his unique identity as a contemporary American artist in New York City. His 2003 seminal exhibition, “Fargo/Far-To-Go” at the Plains Art Museum in Fargo, North Dakota—coincidentally opening on his birthday—brought together all the threads of Paul’s background: his parents’ journey, his childhood in North Dakota, and his identity as a hand papermaker and artist. Paul designed the installation as a ghost-like journey featuring poetic symbols (either made of handmade paper or covered with handmade paper) of birds, which represent freedom, and tigers or cats embodying courage, alongside transfer-print portraits of his family. The haunting message of the past embalmed in paper is juxtaposed with an interpretation of a mid-century American Chinese restaurant with table settings of Chinese dishes opposite typical American place settings. The installation “Far-To-Go” is a masterful synthesis of ancient cultural history, political events, the Asian Diaspora, the immigration experience, the American Dream, and the artist’s ability to create a personal reference through art.

Paul has retired from his day job as a master collaborator, but he has continued to create new art in his signature style that reveals his gifts as an innovative papermaker and his identity as a unique artist.

Become an NAHP Member

Join our vibrant hand papermaking community and access your membership benefits.