DOUGLASS MORSE

HOWELL

PAPERMAKING CHAMPION

1906—1994

Douglass Howell’s lifelong exploration of the potential of papermaking as an artistic medium stimulated the growth and scope of hand papermaking as we know it today.

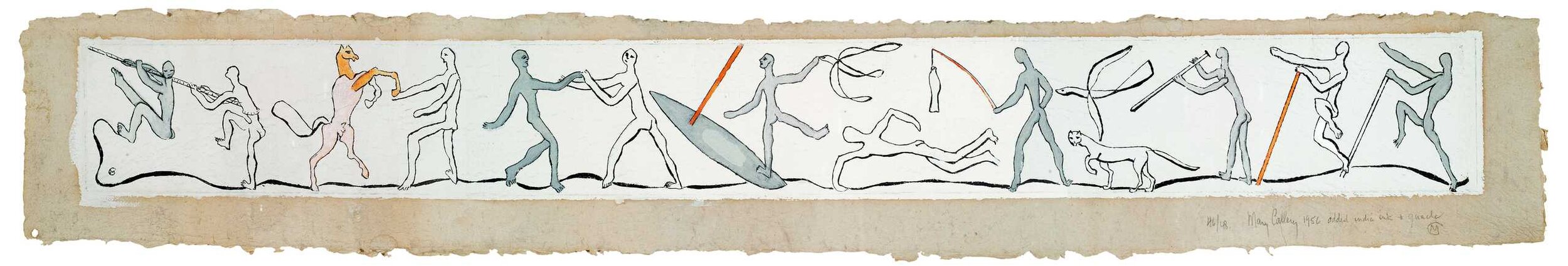

America: mid 1950’s. red and yellow linen. 15.5”x19”.

Douglass Morse Howell

Now Departed Papermaking Champion

1906-1994

While I have not always kept up with developments in hand papermaking, for much of my life I was able to communicate, collaborate, and commiserate with many individuals who have advanced papermaking in America and who have had an impact on innovations in the field. It turns out that I was the last individual who worked with Douglass Morse Howell at the vat. Having written about him in the past I take this occasion to reflect on my memories as a young artist trying to find her way.

In 1978 I did a weeklong workshop with Douglass and continued to work with him through the eighties. The first time I arrived at his workshop it was like entering a creator’s jewel box. The walls were hung with his own and other’s artwork. He had an extensive collection of books and correspondence on papermaking, which were a tremendous asset for any student. Files and piles. The upstairs office smelled like pipe tobacco and the studio smelled fresh and clean. He was a stickler about cleanliness.

Watching Howell at the vat was one of the delights of my life with paper. Not only was Douglass curious, he radiated joy when he was sheet forming. The first time I watched him form a sheet with his well-worn hands, I almost felt like an intruder because he was so deeply absorbed in his craft.

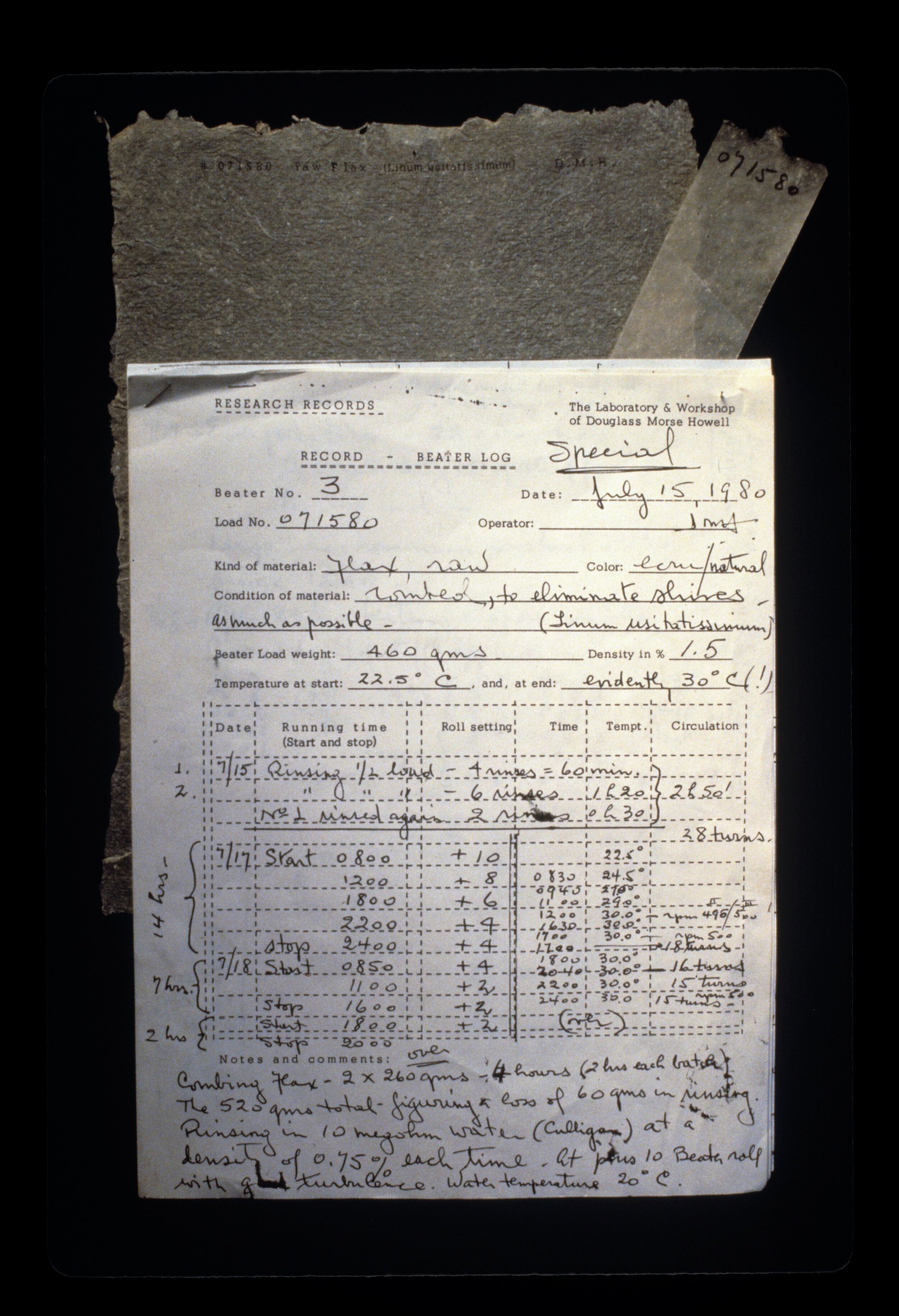

I would travel from NYC to his studio in Riverhead, Long Island, several times a month to learn and assist him with his research. This was a period when he was primarily doing flax studies. I was there when he did a 36 hour and 20 minute beater load of flax. Howell was into his second day at the beater when I arrived one weekend. He asked me to take temperature and circulation readings for the afternoon. His little circulation counter was a cork with wire spokes that he attached to the beater tub with a C-clamp. It had a little red pushpin attached to one of the spokes. The counter revolved as the pulp circulated. This allowed him to measure the number of revolutions of the stuff per minute. You had to be there. As hydration progressed the circulation would slow. Between the sound of the beater and watching the spokes, I was fully mesmerized. On an afternoon like that Howell would typically be upstairs typing away while I worked downstairs.

Howell should undoubtedly be championed for his design of a beater which could process raw flax, hemp and damask rag, paving the way for his own and others artistic innovation. He had 3 beaters built, the first in 1946, and improved the design with each one. In his management of the beater I would submit that he was a “bruiser,” not a “cutter”. Though western in his approach, he understood our Asian heritage. He preferred to pound like a mallet and tried to figure out how to do that with a beater. This made stronger paper. He combed the raw fiber into balls which were fed into the beater slowly. He didn’t cook fiber, but sometimes drained and changed the water three or four times early in the beating process. That 36 hour pulp was still somewhat stringy when he stopped the beater because he had taken the roll down so slowly.

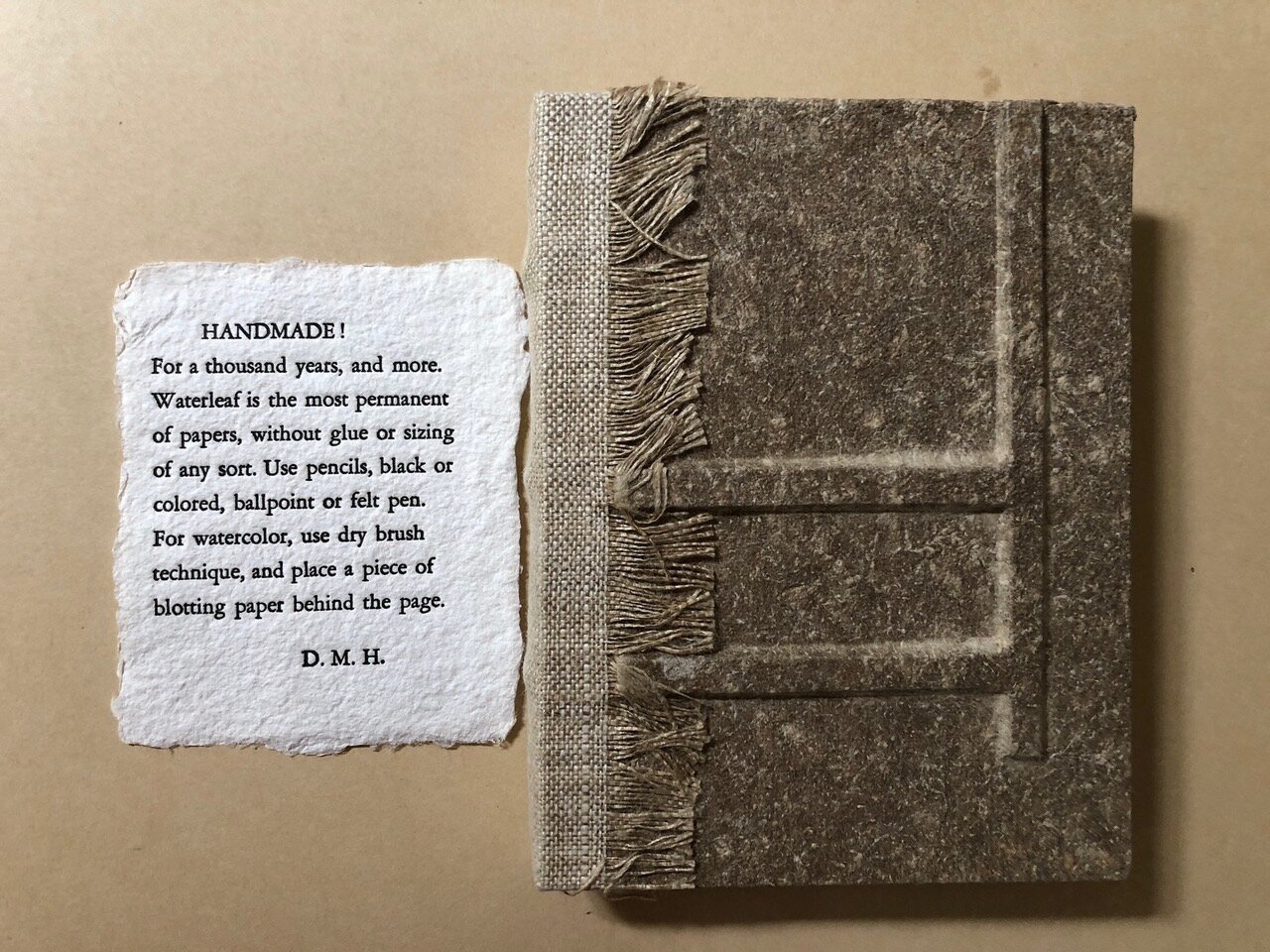

Howell did not use additives, but preferred to use dyed linen for color work. His sheets were loft dried or they were dried and peeled off the mould. All of his sheets were waterleaf. He would tub or brush on sizing later, if needed. Howell did quite a bit of research with pigment and sizing, and made several watercolor studies on linen papers with varying degrees of beating, always taking notes.

Always taking notes.

— Eugénie Barron

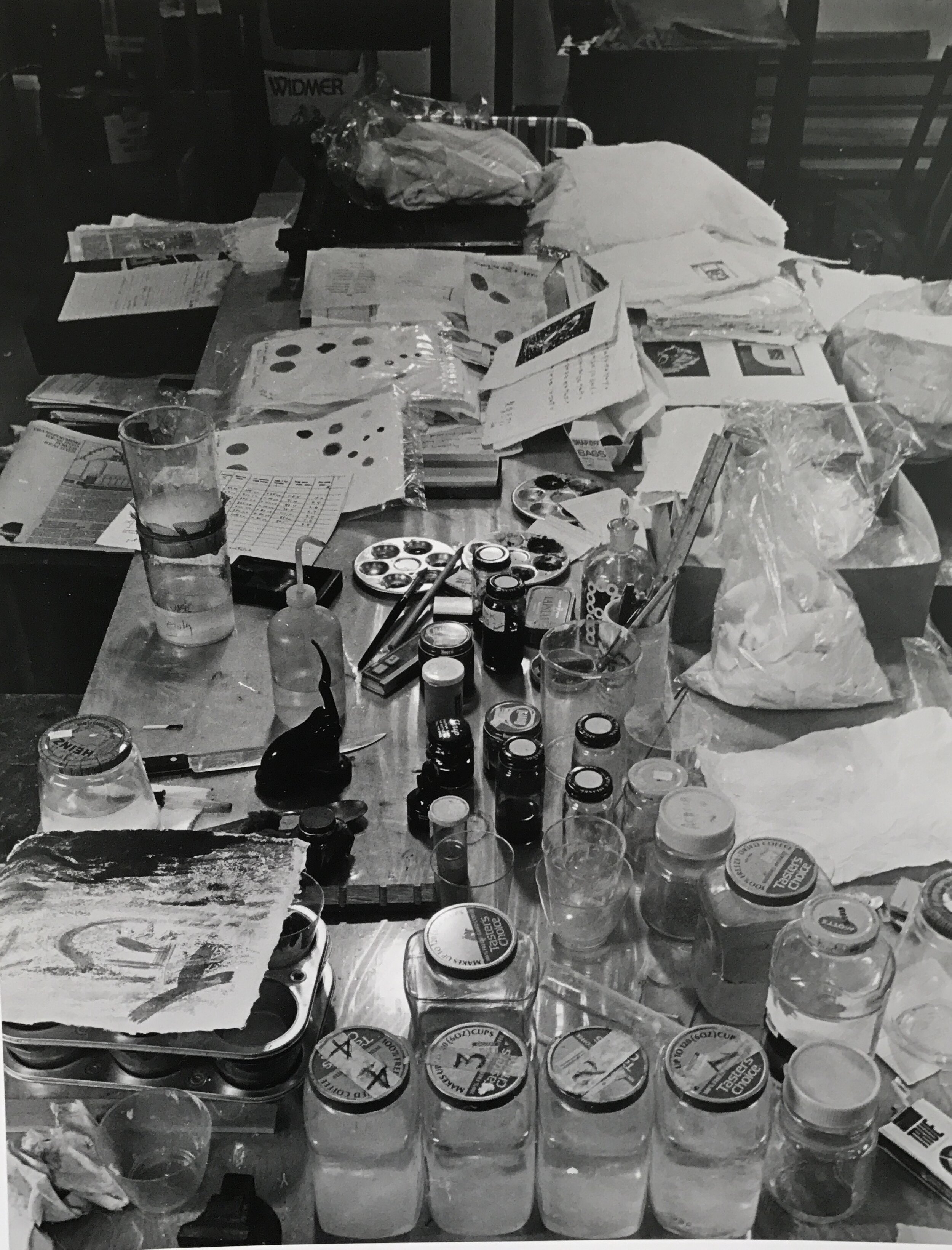

Riverhead, NY workshop. early eighties. photo Frank Paulin.

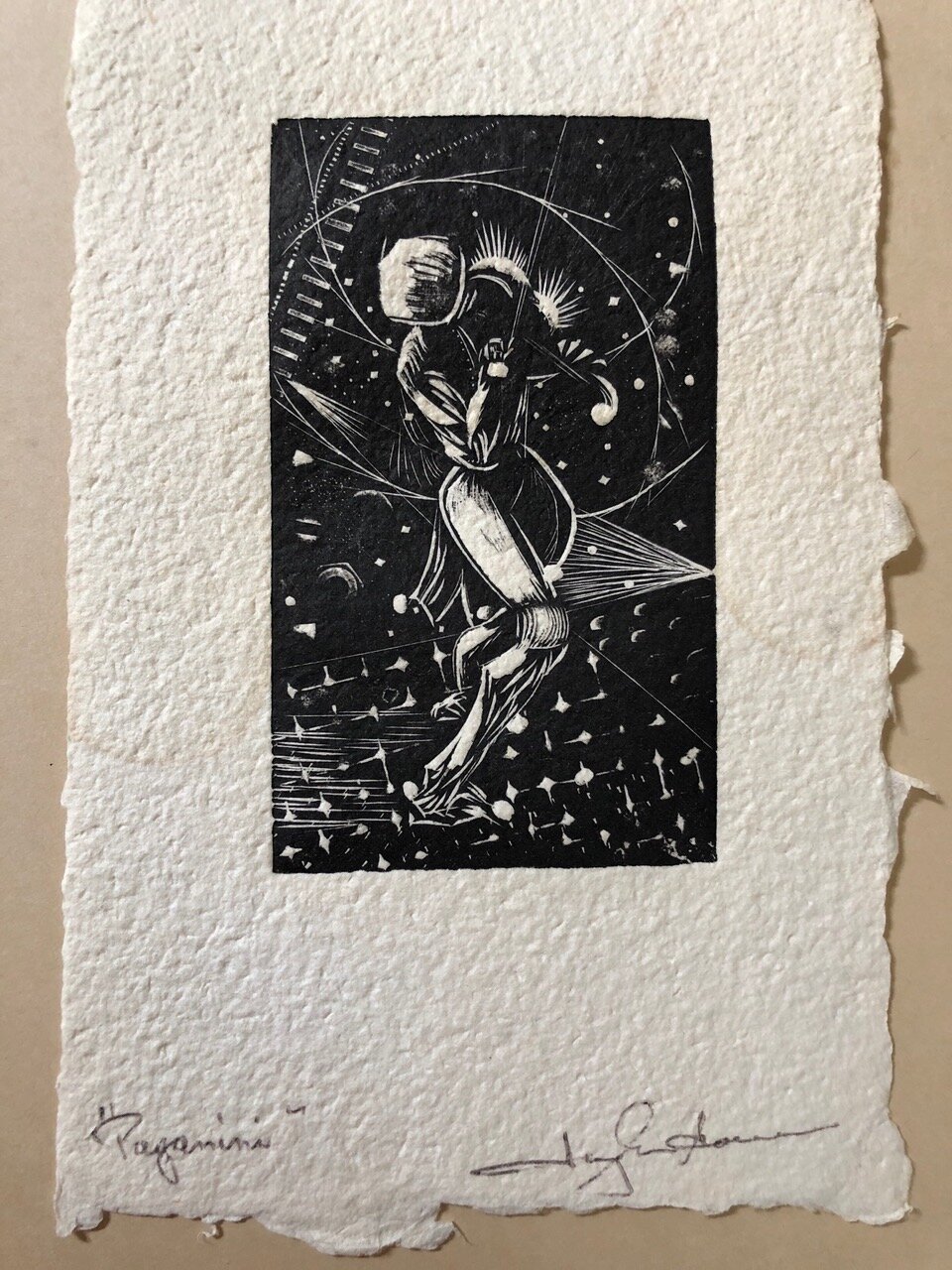

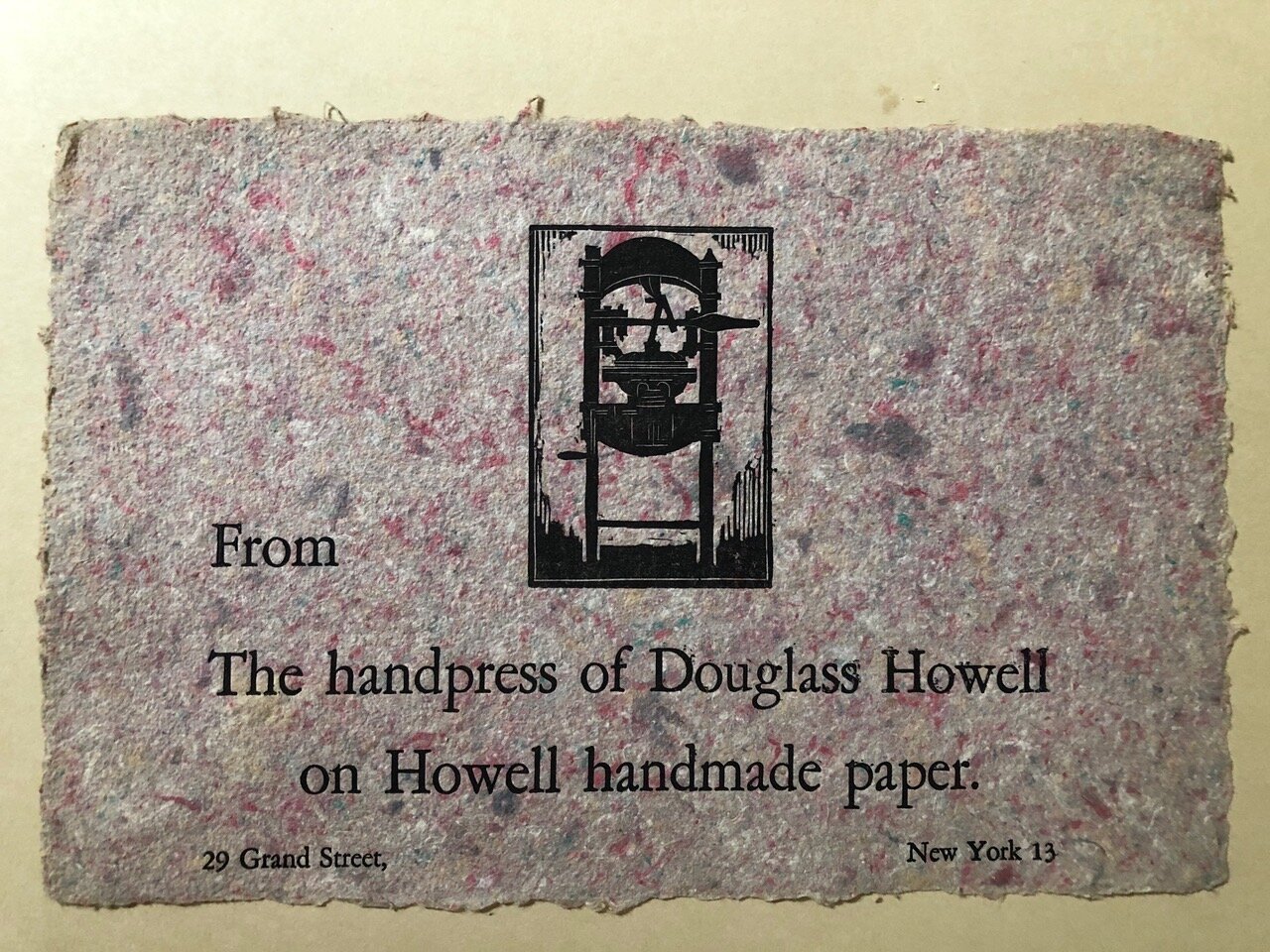

By Hand: photo collage of Howell printed papers for promotional postcard. photo Elizabeth Howell King.

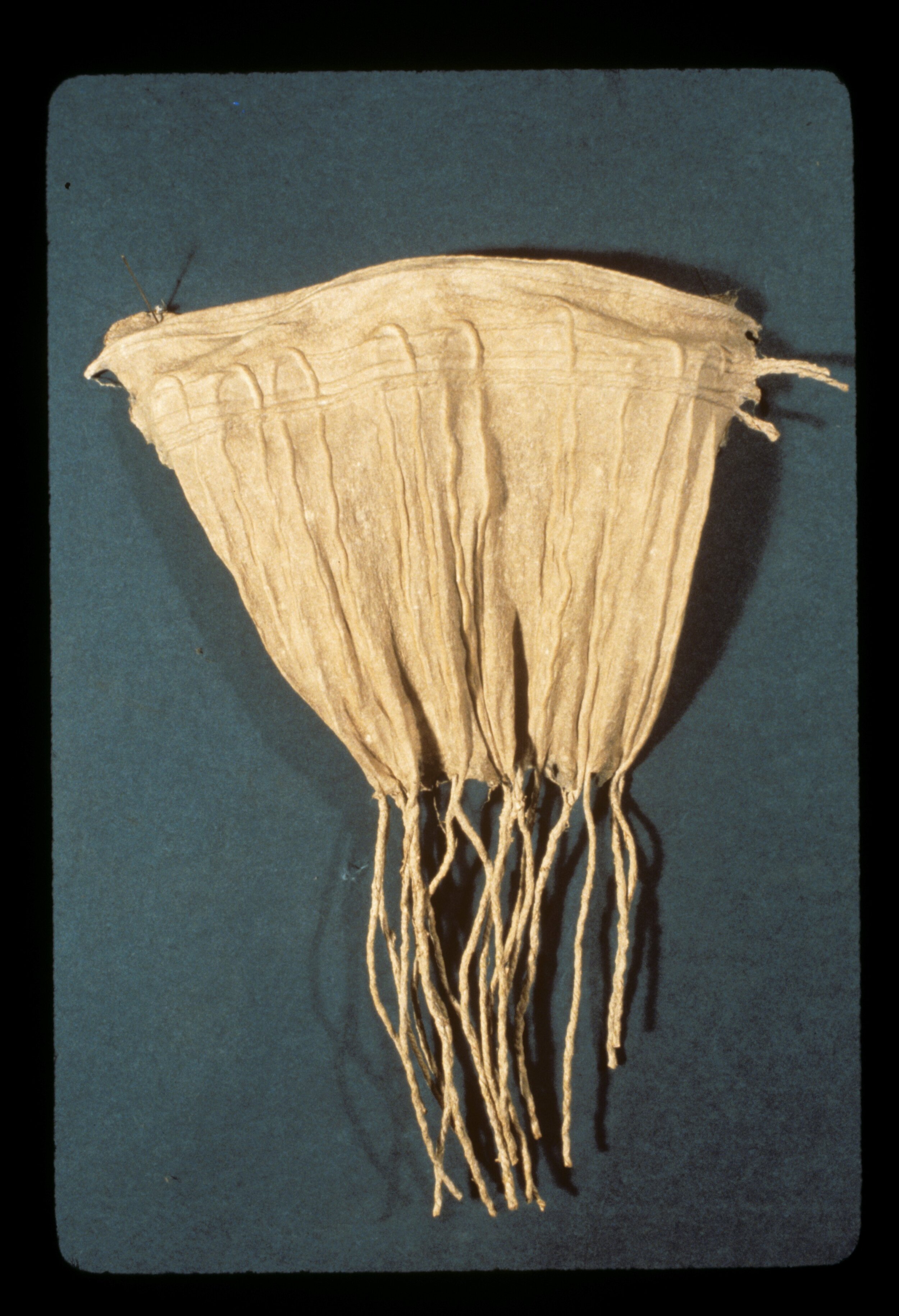

1979. linen with string. 9”x10”.

Testing Table: Riverhead, NY workshop. 1982. photo Michael Paulin.

photo of first page of 36 hour flax beater load notes. 1980.

Douglass Morse Howell

For North American hand papermakers, there are two 20th century pioneer papermakers who are acknowledged with resurrecting hand papermaking. Dard Hunter revived it and Douglass Howell reinvented it. Making paper by hand was extinct in the United States by the mid-19th century. It was not until 1912 that fine book printer and publisher, Dard Hunter reestablished the craft of fine hand papermaking. His appreciation and practice of the craft are well documented in the numerous books he wrote and produced. Hunter revived the craft but was not able to sustain the business of making sheets of paper. By the 1930’s when Hunter abandoned his second attempt to establish a hand papermill, the practice of hand papermaking lapsed in the United States.

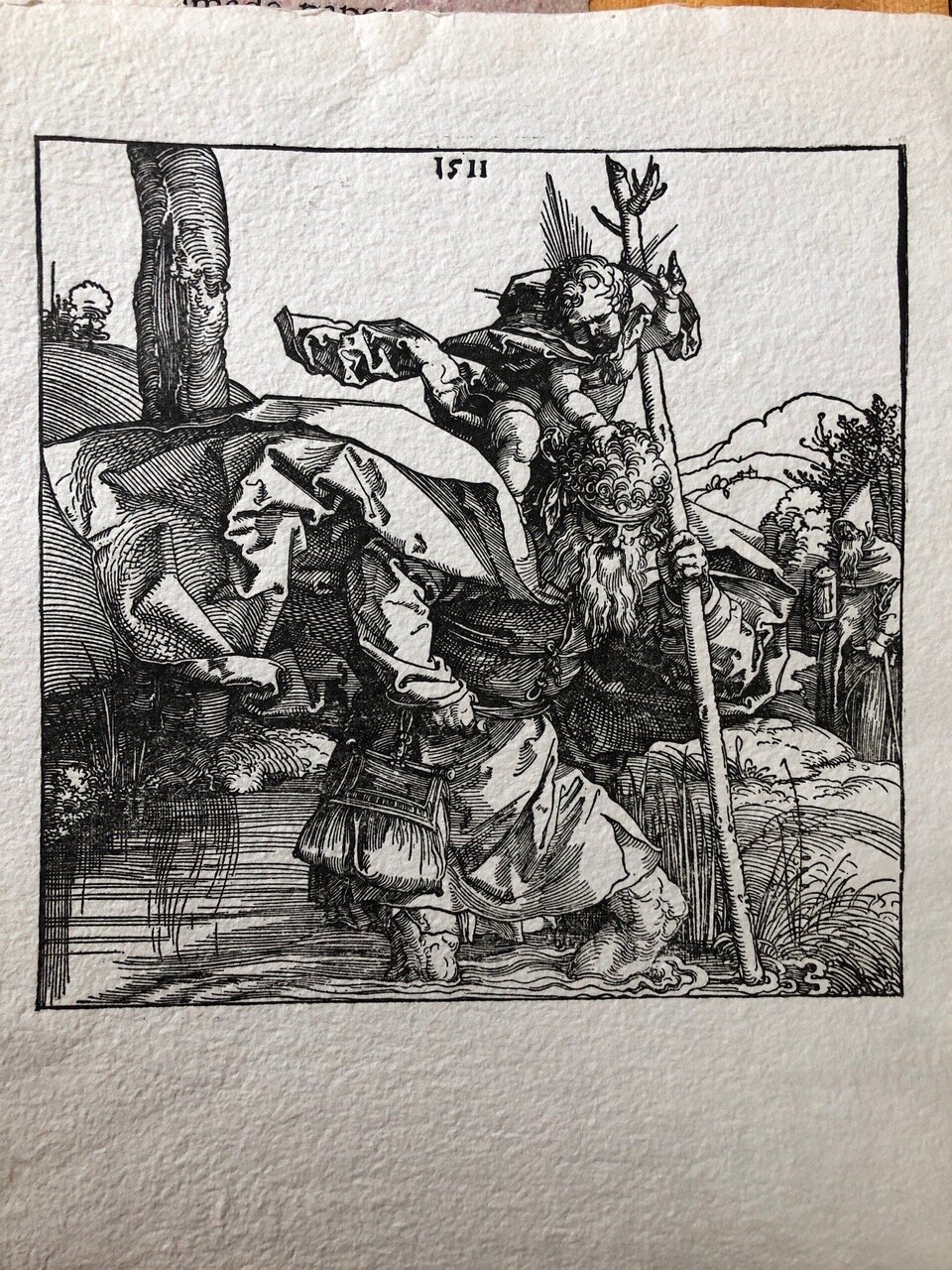

More than a decade later, when Douglass Howell returned to New York after World War ll and established himself as a fine printer, he discovered that artist quality paper was in short supply. He became interested in producing his own paper and researched Hunter’s books on hand papermaking at the New York Public Library. Following Hunter’s guidelines, he built the equipment and established a hand papermaking studio in Soho, in downtown Manhattan. Howell concentrated his early efforts on making fine paper from linen rag for his own printmaking and eventually for other artists. He designed custom paper for artists such as Mary Callery, Stanley William Hayter and Jackson Pollack. Working closely with print publisher, ULAE, he created edition paper for artists such as Larry Rivers. As Howell tirelessly experimented and developed unusual sheets of paper from linen rag, he began to create his own highly original handmade paper art. Using different colors of dyed rag, he created a palette of colored pulp to design pulp paintings and collages. These breakthrough pieces, “papetries,” were exhibited at The Betty Parsons Gallery in 1955. Howell went on to explore the use of paper pulp to make sculptures and unique books exhibiting them in the 1980’s at The American Craft Museum and The New York Public Library.”

Though Howell made custom sheets of paper for other artists, he did not act directly as a collaborator using the papermaking process to assist others creating their art. He shared his knowledge of the craft and his technical and artistic experiments with interested students in workshops and tutorials. In 1961, Laurence Barker, printmaking professor at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, took a weekend workshop with Howell. Inspired by Howell’s innovative approach to hand papermaking, Barker established a student papermill for his printmaking students at Cranbrook. Barker’s students including, Winifred Lutz, Aris Koutroulis, Walter Hamady and Tim Barrett went on to establish the first university level hand papermaking programs in the United States. From these university programs, studios such as Twinrocker grew into a business making fine sheets of paper, The University of Iowa Center for The Book evolved into a laboratory for limited production of conservation paper and Dieu Donné developed into a papermaking fabrication studio for international artists.

Dard Hunter is rightfully credited with reviving hand papermaking in the United States helping to reestablish an appreciation of and market for fine handmade paper. Douglass Howell’s lifelong exploration of the potential of papermaking as an artistic medium stimulated the growth and scope of hand papermaking as we know it today.

When Tim Barrett, Paul Wong and I went to visit Douglass Howell at his studio in Riverhead, NY ten years before he died, the three of us had been studying hand papermaking and developing our role in the field for many years. Douglass welcomed us enthusiastically to his busy studio and generously shared as much as he could from his decades experimenting with linen pulp and paper. We learned much and I think he was pleased with the camaraderie and passion we shared. Decades later, I can still see his expression as he questioned each of us about our dedication, looking us in the eye as he asked for a vow of commitment to continue to explore and expand the field. I think we have, with great respect for his ground-breaking work.

— Susan Gosin

Untitled Papetrie (grid): mid-1950’s. red and white linen with string. 12’x17”.

Early Flax sculpture: date unknown. flax pulp, wood, string. dimensions unknown.

Howell Beaters: Riverhead, NY workshop. 1982. photo Michael Paulin.

Become an NAHP Member

Join our vibrant hand papermaking community and access your membership benefits.