DAVID REINA

PAPERMAKING CHAMPION

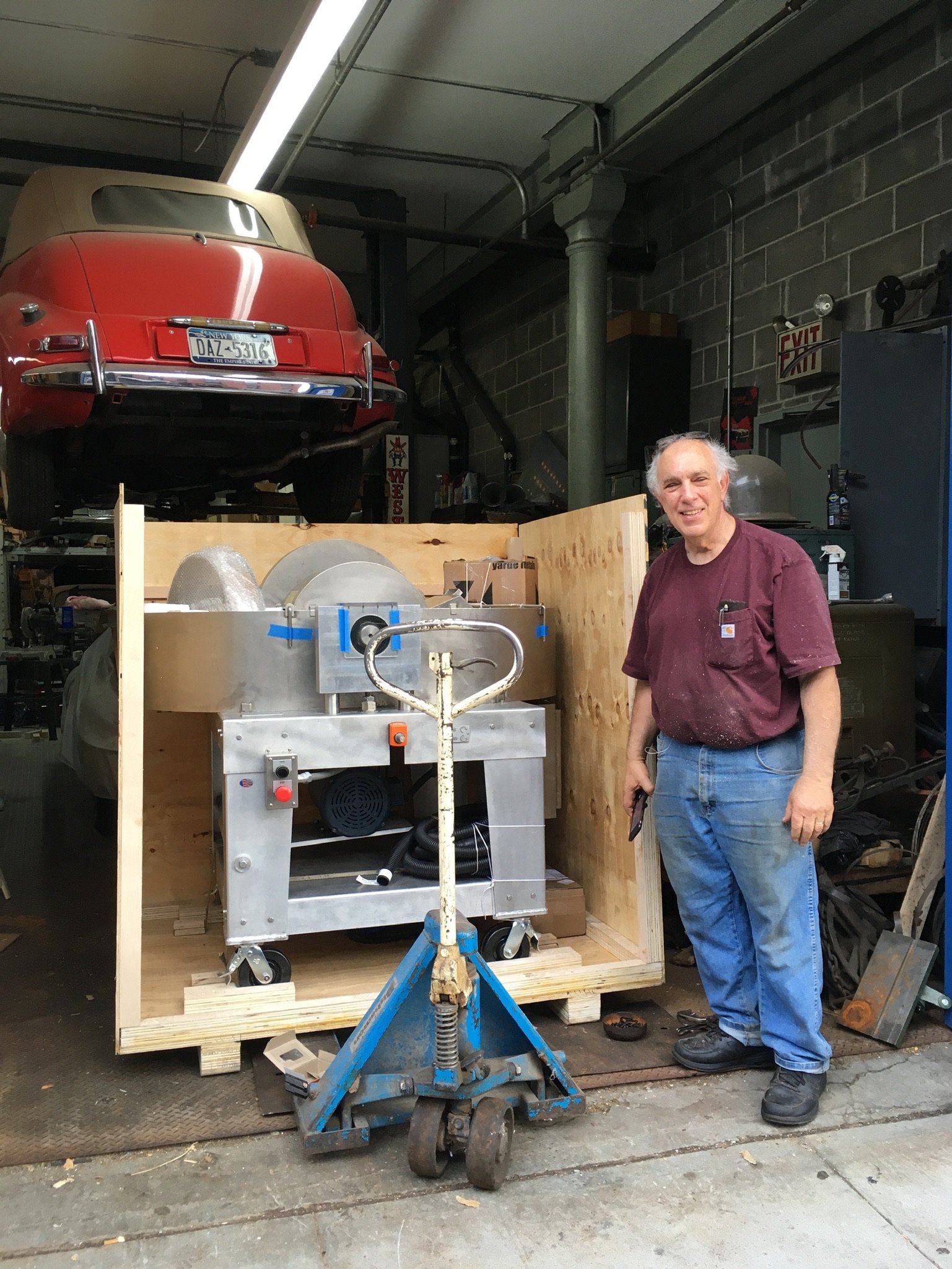

Over the past 47 years, papermaking equipment designer and fabricator David Reina has built or overseen the production of 425 two lb. beaters, 15 seven lb. beaters, 10 ten lb. beaters, and two naginata Japanese-style beaters. In addition, he has produced 20 presses, 23 vacuum tables, and 30 dry boxes. Reina’s careful attention to user safety and convenience, reliability, and performance has been a component of each piece of equipment. He has shipped his products to 19 different countries. All told, Reina’s specialized papermaking equipment has helped keep our craft humming on a daily basis. Without his efforts, our field would not be as active, productive, and healthy as it is today.

David Reina

Essay by Tim Barrett

Note: The following brief essay is a collection of thoughts and reflections on the life and work of my colleague—our colleague—David Reina. It is not comprehensive or detailed, but fortunately for readers with an interest in learning more about Reina and his story, Aimee Lee’s excellent chapter, “The Toolmakers – Those Who Build So We Can Make, Part I: Timothy Moore and David Reina” in Papermaker’s Tears: Essays on the Art and Craft of Paper, Vol. 1 is readily available. My comments below draw heavily on Lee’s essay, as well as on my 75-minute interview with Reina on November 28, 2021.

With people whose work I admire and respect, I am always interested in what happened during their very early formative years. What were they curious about? What activities or projects did they undertake when they were in their teens and early twenties? David Reina’s early suspicions, activities, and creations, I think, could be a window into how he came to be the builder of the trustworthy papermaking equipment we know so well.

Reina’s parents were both artists and art teachers; his mother was a painter and his father a sculptor. As a teenager, Reina had ready access in his father’s studio to tools and power equipment when he had the urge to make something. He once removed the metal body from a Crosley automobile and spent many days and late nights out in the studio building a “woodie style” new body for the car, which he ended up driving to college. The mechanical and design aspect of cars interested him from an early age. He bought his first car, a 1936 Oldsmobile coupe, at age 11, but was forced to give it up in 7th grade due to his dropping grades. (He still enjoys this hobby today and owns an eclectic mix of vintage cars.)

Reina also received free flowing parental advice on his creative activities when he requested it. In high school he earned many As in art and industrial arts classes, but more sporadic grades in other subjects. His interests were already focused. After high school, he attended State University of New York–New Paltz, with a focus on painting and etching as well as art history and art education. Aimee Lee’s summary of Reina’s activities at this stage in his life indicates that after college he lived with his parents on Long Island and tried, unsuccessfully, to make a living illustrating children’s books and making wooden toys. Eventually, to bring in more income, during the week he worked for a company that fabricated tow trucks, wiring truck lights, and on weekends, he was a guard at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design).

A year of seven-day-a-week work for low wages convinced him he had to find his career path. A friend of a friend arranged for Reina to visit a group of people who made prototypes of new commercial toy products. He realized immediately his career path. It involved daily design problem-solving, sculpting, engineering, and finishing toys to a high commercial level. Reina stayed with this field and at one time was the Director of R & D at Buddy-L toys. That position took him to Hong Kong and China to work with the company’s development teams. Because of that position he was asked to teach a class in prototype construction for a new accredited toy design program at the Fashion Institute of Technology in Manhattan. He found engaging with his students in the classroom to be very satisfying. He taught the same weekly class for 29 years, retiring only recently, just before Covid arrived.

The toy industry was a commercially challenging business with all of the ups and downs of putting a product before the public. Building papermaking equipment, on the other hand, started casually for him and developed into a “cottage industry” over many years, with a very different vibe than the toy industry. For Reina, it provided a link to the world of artists and also satisfied his interest in building his own products.

His early interest in papermaking started in his sophomore year of college (1973) when he was introduced to Anton Krajnc, an Austrian teacher and artist who was dating and later married a New Paltz student friend. Shortly afterward, Reina left for a semester of study (including etching) at a program in Urbino, Italy. Krajnc was nice enough to offer Reina the loan of an etching press that he had stored in Urbino.

In the summer that followed his trip to Urbino, Reina was contacted by Krajnc who was sharing a studio with Douglass Howell in Lattingtown, NY. Krajnc relocated there for the purpose of learning papermaking from Howell. However, for the talented and eager Krajnc, the lessons proceeded too slowly. Sometimes the lesson was more about how to run the table saw and not how to beat fibers for paper. Over a restaurant meal with Reina and some wine, Krajnc wished out loud that he had his own Hollander so he could learn at a faster pace. Reina had seen the three beaters that Howell had made by hand. He was fascinated not only by the machines but also how the water and fibers morphed into pulp for paper. Reina suggested that he make one for Krajnc. They agreed on a price of $600 for Reina to fabricate the beater. The design was based partly on Howell’s beaters and questions posed to Howell, combined with details on Hollander beaters from Dard Hunter’s book Papermaking, The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft. As Reina’s folks were then traveling in Europe, he had unfettered use of his father’s studio. He worked on the beater for a month, spending all of his budget on materials and local machine shop help. Surprisingly, the finished machine worked well. This was apparently a bit disconcerting to Howell, who, at the time (circa 1972) was developing a reputation in the new community of small workshop hand papermakers and paper artists. It probably did not help matters that Krajnc soon had many papermaking students of his own, including Coco Gordon, a Long Island artist who became seriously involved in papermaking.

Over the next 40 years or so, while Reina worked in the toy development and production industries, he also continuously refined his beater designs, and built and sold machines domestically and abroad. Collaborative work with skilled machinists helped Reina learn to build better machines, and he assigned various components to different shops so that he could attend to final assembly and design innovations. Eventually, in the mid 90’s, the stress of deadlines in two different industries was too much, and Reina decided to commit 100% to designing and making papermaking equipment.

In addition to his reliable workhorse beaters, Reina developed specialized pieces of papermaking equipment, including a Japanese-style naginata beater, drum-type washers for his beaters, and a hydraulic press specifically designed for papermakers. The press features a wheeled cart that, once loaded with a heavy stack or “post” of wet felts and paper, can be easily rolled into the press. As pressure is applied, expelled water is collected by a built-in stainless steel catch pan fitted with a drain that directs the water to a bucket or other location of choice. (A pleasure to use!)

Over the course of his career, David Reina produced 450 beaters of various capacities, and an additional 73 pieces of other equipment including vacuum tables, presses, and dry boxes. Equipment has been shipped to 19 different countries. More than the impressive count of pieces of equipment, what I find most significant is the innate engineering and design aesthetic evident in Reina’s work. His machines not only work well and safely, they incorporate a uniform approach to quality materials and skilled workmanship, and careful attention to user-friendliness. The combination leaves owners around the world feeling a combination of pleasure, honor, pride, and luck when working with a piece of David Reina equipment.

Postscript:

Reina was 68 at the time of this writing (2021). He would like an understudy to learn and take over the business, but the path forward is unclear. The understudy would need to be an individual, he says, with skills in various shop specialties like woodworking, machine shop techniques, precise measuring, welding, and the ability to learn quickly and work under deadlines. Even if such an individual steps forward, how would the business be transferred? What about the equipment and the needed workspace? Reina says it would take a two year cycle of working together to go through all the different machines and build processes. The machines cost a lot, but quality materials and build costs are a major part of the final price. Reina hopes the right new builder may come up with ways to streamline construction of the machines.

How such a working relationship might unfold is unknown but I find it heartening and encouraging that David Reina expresses an openness and enthusiasm to share his skills and ideas with someone younger.

Become an NAHP Member

Join our vibrant hand papermaking community and access your membership benefits.